Fr Neil’s homily at Mass on Trinity XIV (13 September)

None of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself. If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord; so then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s.

Christ is continuing his dialogue with the disciples upon the theme of the inner life of the ecclesia, the Church.

Last week we saw how the community, marked by the character of love, was to deal with the unrepentant sinner in staged ways. The final action, if all other ways failed, would be excommunication. This week we see Peter asking but ‘what about the brother that does repent; how many times am I to forgive him? Seven times?

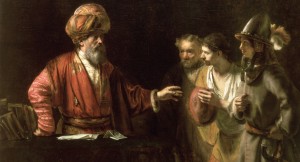

Peter isn’t randomly choosing a number but what was seen as the perfect number — seven. It would seem that Peter thinks this would be a really generous act to forgive a person seven times, and it would. Have you tried it? It is difficult to grasp the shocking nature of our Lord’s reply: “I do not say to you seven times, but seventy times seven.” For those with good maths that equals 490 times. However, Christ is not asking us to keep a tally but making the point that forgiveness is a continuous ongoing process that never stops. Therefore at the heart of the ecclesia, the Church, there must be a ready stream of mercy and forgiveness for the repentant sinner. To illustrate the point he is making, Christ goes on to tell the parable of ‘the unmerciful servant’.

Our Lord’s use of hyperbole in this parable makes the point very clear. The servant’s debt is 10,000 talents. It’s a massive amount of money. One denarius is about a day’s wage and 6,000 denarii make one talent. For the servant to pay back his debt to the master at a day’s wage would take him 164,000 years! It’s two thousand years since Christ, so he has only another 162,000 years left of debt.

We get the point that the Master forgave the servant a debt that was impossible for him to pay back. One might expect in the light of such generosity that the servant would be a changed man. However, as shocking as the cancelling of his debts was, equally shocking is his treatment of the person who owed him 100 denarii. He is not merciful or forgiving, despite his fellow servant imploring him for mercy as he had implored his Master. He has his fellow servant sent to debtors’ prison.

The master, when he hears about this incident, is furious with his unmerciful servant and has him sent to prison too. The point that Christ is trying to teach his disciples is that this is exactly what “my Heavenly Father will do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother from your heart.”

The Church is made up of members who have been forgiven a debt that we are incapable of paying ourselves — even if we were given all eternity to do so. The Fall created in us a brokenness in ourselves and an alienation from God that we could never fix. The heart of the Gospel message is that what we were unable to do, God — in Christ — has done for us by his death on the Cross. Healing, forgiveness and redemption are now freely given to the repentant sinner who implores the Lord to forgive their debt. It is not insignificant that Christ when teaching his disciples to pray uses this same language in the Lord’s Prayer: “forgive our debts as we forgive our debtors”.

The sacraments are the most powerful form of God’s merciful ‘love in action’ that we encounter. That which he does for us, readily every time we seek his mercy, we are to emulate in the manner that we live out our lives.

Mercy and forgiveness for the body of Christ is not a optional extra but a critical element of its life. Without it there is no real reconciliation or eternal life; “Go and learn what this means, ‘I desire mercy, and not sacrifice.’ For I came not to call the righteous, but sinners.” And in the beatitudes he says, “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.”

What is expected of the servant is that, in his fealty to his master, he is bound to faithfully emulate his master’s will as a part of his loyalty. Paul speaks of this in our epistle reading. ‘None of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself. If we live, we live to the Lord, and if we die, we die to the Lord; so then, whether we live or whether we die, we are the Lord’s. The lordship that Paul is referring to is that, (CCC 668) “He is ‘far above all rule and authority and power and dominion,’ for the Father ‘has put all things under his feet.’”

When we were baptised and entered into the Church, we willingly gave up our lives by entering into Christ’s death and resurrection and thus received the pledge of eternal life. In so doing we have acknowledged Christ as Master and Lord of our lives rather than ourselves. As Paul says in Galatians: “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me; and the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.”

There is no neutral ground here. Either we are slaves to sin or slaves to righteousness. For “Christ is Lord of the cosmos and of history. In him human history and indeed all creation are ‘set forth’ and transcendentally fulfilled.”

As subjects of the Kingdom then we are bound to forgive our penitent brethren because our Master and Lord has told us to.

Yet our forgiveness of our penitent brother is motivated an enriched by a response of gratitude in the light of the merciful love revealed to us at the Cross. Our Lord embraced the cross so that we might be reconciled, forgiven and enter eternal life. To embrace such a divine gift requires us to let go of resentment and wrath. Such bitterness allows no room for divine grace and mercy.

Quite simply — we forgive because we are forgiven; we show mercy because our Lord has shown us mercy; and we love because our Lord has first loved us, in whose service we find our perfect freedom.

Posts

Posts