Fr Neil’s homily at Mass on the Second Sunday of Easter (11 April)

“My Lord and my God!”

These are the profound words of Thomas as he encounters the risen Christ for the first time. Thomas has somewhat unfairly been labelled as ‘doubting Thomas’. He earned this name for not believing the witness of the other disciples to the risen Christ. Of course Thomas was not unique in his disbelief, as in Mark’s gospel all the apostles had refused to believe the witness of Mary Magdalene and were reproached by the Lord for ‘their incredulity and obstinacy’.

Did Thomas, in demanding signs, do anything more than what we would have done in his place? It’s all to easy to be swept along with the crowd and get caught up in wishful thinking. Perhaps it mattered too much to Thomas to allow that for which he hoped and yet daren’t believe to be decided by the thoughts of others. It’s not surprising that he should say, “Unless I…place my fingers in the marks of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe.”

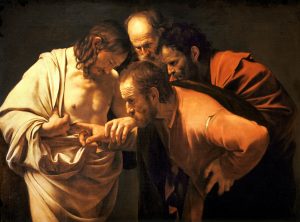

Thomas might have been using hyperbole in his rather dramatic statement to the other apostles. But with our Lord’s appearance, he is forced to make those words a reality. “Put your finger here and see my hands, and put out your hand and place it in my side.”

Thomas is left in no doubt about the physical reality of the resurrection of Christ. This is not just a nice idea, group delusion or hysteria but concrete reality. This physicality of the resurrection is fundamental. Our faith is incarnational: it cannot be reduced to a set of philosophical ideas, however good they are.

Jordan Peterson, a clinical psychologist and social commentator who is not a Christian, uses the Judeo/Christian narrative to combat some of the extraordinary excesses of some modern-day thought and movements. However he is terrified that the narrative and the history might be one, that the narrative is true. He sees the consequences of that as being overwhelming.

Yet the Church rightly and deliberately roots the events of Christ, our salvation, in history. Pilate gets a mention in the Creeds exactly for this reason: to fix our belief in events that took place in time and space. We are not afforded the luxury of being existentialists, toying with ideas alone, but are called to live out that which we believe in our lives. It requires the conversion of our lives after the teaching and manner of Christ.

This embodying of our faith is why — however sophisticated live streaming of mass becomes — it cannot in anyway substitute being physically present at the representing of the sacrifice of the mass. The use of holy water, crossing ourselves, genuflecting before the Real Presence and the receiving of Our Lord in the sacrament are fundamental to our embodied faith.

Our reading from Acts then is not some primitive Socialist or even Communist manifesto, but a lived-out faith that responds with generosity of heart to our brother and sisters in need. It is the realisation that we must bring the internal self and our bodily existence in line with Christ. It is this that marks out the saints and is the means of our salvation. One of today’s great heresies is that the inner life and the body are separate realities often in conflict with each other. The Gospel speaks so profoundly against this. In Christ the spiritual and physical, heaven and earth, are reconciled. The inner conflict caused by the Fall has been overcome in his life, death and resurrection.

Of course some might say “…but Thomas and the apostles were privileged to walk, talk, and eat with Christ, they heard his teaching, saw the miracles and his crucifixion, burial and resurrection.” Yes, they were blessed to be witnesses to these events and as a consequence most were martyred because of it. However, our Lord offers a blessing for those who have not seen and yet believed.

Yet we also occupy a special position in that, as an Easter people, we have the whole of scripture, the Magisterium, the teachings of the Church and the witness of the apostles and saints throughout the ages that help unfold the revelation of the mystery of the resurrection. As Christ himself taught in relation to Lazarus and the rich man, “if they do not hear Moses and the prophets, neither will they be convinced if some one should rise from the dead.”

But of course we do encounter the risen Christ — what is it that we think we are receiving in the Eucharist, if it is not the body, blood, soul and divinity of Christ? That which we receive upon our tongue and take into ourselves is Christ, our life. We in turn are witnesses of these things and are called to take that which we have received unto the world that is lost without it. Let us reflect on this supernatural reality we participate in by saying to ourselves as we come to receive, that great confession, ‘My Lord and my God.’

John is at pains from the beginning of the gospel to to help us understand the physical and divine nature of Christ and that they matter — In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and was God…..and the Word became flesh and dwelt among us. Throughout the gospel we have the ‘I am’ sayings that refer back to the divine Name revealed to Moses at the burning bush. As if to book end the gospel, Thomas’ encounter with the physical resurrection of Christ leads to him to proclaim ‘my Lord and my God’. As John states himself ‘these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may life in his name.’

The editorial title to this article is a phrase from the Easter Sequence Victimae Paschali laudes attributed to Wipo of Burgundy (11th Century) in the customary English translation.

Posts

Posts